27 April 2020

Note the reader:

This interview is a follow-up of our 2019 study: Data breaches in Healthcare; The attractiveness of leaked healthcare data for cybercriminals

Yes, this is still the case. It’s about centralizing reporting regarding data breaches in healthcare and making them publicly available. The U.S. has the healthcare regulation Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in place then makes the information about the breaches publicly available. A European equivalent to HIPAA could be the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). But they do not publish data breach incidents as the HIPAA Journal does. That’s why most of the data is from the U.S.

However, we see news articles on incidents and breaches within Europe, and thus we are sure that data breaches within the healthcare sector in Europe are as persistent as in the U.S.

We are theoretically speaking, yes. Health data contains a lot of information that can be leveraged in different ways. We will never know for sure what a malicious actor intends to do with the health data they have extracted. But a lot points towards financial gain as motivation and identity theft, which could then be used for fraudulent activities, most often resulting in monetary gain.

We have learned from last year’s research and looking into new data collection right now that it’s not only a multitude of information within health data (e.g. patient records) that can be leveraged, the stolen data from the health sector itself can vary. As an example, last year, we were only looking for breached health data. We wanted to find out how much they are worth and get an idea of how they would be leveraged. What we also discovered was “doctor fullz”. These listings would help an attacker pretend to be an actual medical doctor and create fake insurance claims. This time, we have come across other stolen or manipulated data from the healthcare sector published in more detail in our upcoming white paper by the end of this year.

Besides the two motivators of financial gain and identity theft; intention to inflict physical harm, targeted or not, is not seen in our data (yet). In September 2020, we witnessed one of the first known cases of a death indirectly caused by a ransomware attack.

Consequently, the potential to leverage health data in multiple ways is there, and the future will probably bring more ways to exploit them.

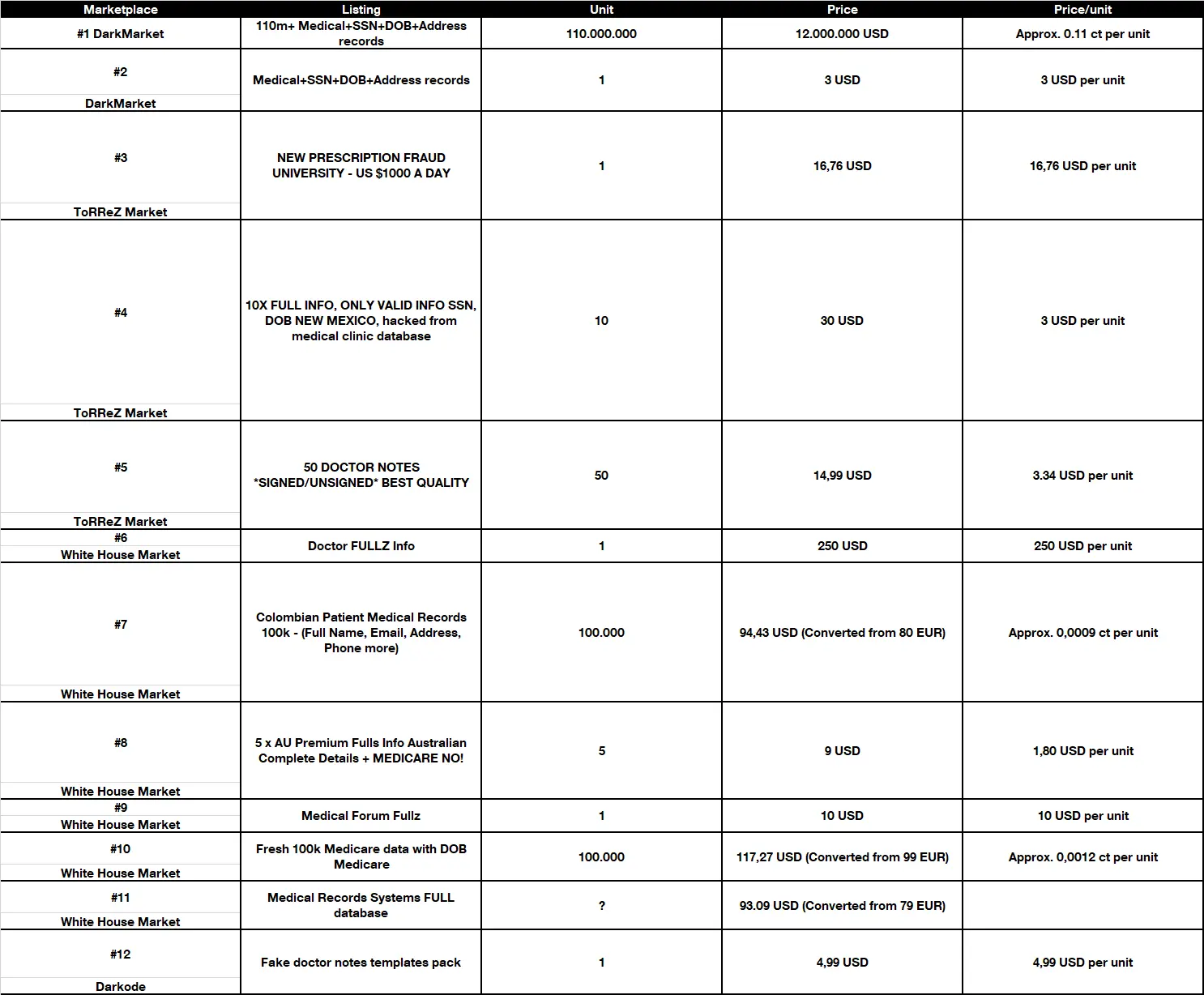

The price of health data varies significantly between listings depending on if a vendor offers one unit or a whole database of health-related data.What we have found is that depending on how much information a listing includes; health data is already offered for a price of 3 USD per unit (see listing #4) when it’s sold in a very small quantity and it “only” includes Personal Identifiable Information (PII) such as Social Security Number (SSN), Date of Birth (DOB) and address and such.

The price will go up as soon as medical data is included, such as in listing #3, which offers prescriptions, or listing #6, which offers “doctor fullz” for 250 USD. On the other hand, batches such as listing #1, #7 and #10 have a low price per unit, but the assumption here is that the vendor is hoping to sell the whole batch, which then would return a price of 12.000.000 USD (#1), 94,34 USD (#7) or 117,27 USD (#10). Listing #2 is one record extract from the 110 million records of listing #1. The vendor would either sell one record for 3 USD or the whole batch for 12 million USD.

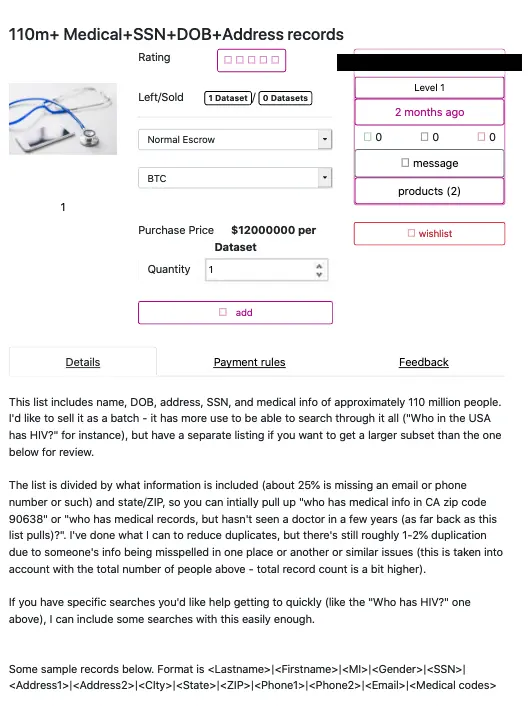

The first listing has an unproportionally high price to the other listings. The reason is that the seller claims to have medical + PII data of 110 million U.S. citizens (see screenshot).

Looking at the prices where we have both price and unit, the average price of health-related data is 26,63 USD per unit. This is still approx. 10 times higher of what we see when looking at stolen credit card details or “only” fullz, including PII data.

We have not found any indication that this is the case. That said, we do not claim to be able to see everything on the darknet either. It’s such a dynamic place, and while a lot has happened in the last 1 to 1,5 years on the darknet, for example, some of the leading marketplaces we checked last time have completely disappeared (via exit scam or other reasons); the time passed since the health crisis started might not be long enough to drive change in demand and price. If anything, some groups announced to pause with their activities due to the ongoing health crisis. This was mostly the case for some major ransomware groups such as Maze, Nefilim & DoppelPaymer. Some even say that if healthcare systems were accidentally encrypted, they would provide decryption free of charge.

However, not all the ransomware groups felt so magnanimous when it came to healthcare providers during this pandemic. One recent incident impacted the Universal Health Services network of hospitals, primarily based in the US. Their systems were allegedly encrypted with the Ryuk ransomware. However, they claimed that no patient or employee data appears to have been accessed, copied, or misused. A more recent example concerns the University Hospital New Jersey in Newark, attacked by a ransomware operation known as SunCrypt. In this instance, the attackers claimed to have 240 GB of stolen data; after an archive containing 48,000 documents was publicly posted, the hospital negotiated to pay a ransom of USD 670,000 to prevent any more patient data from being published or potentially sold.

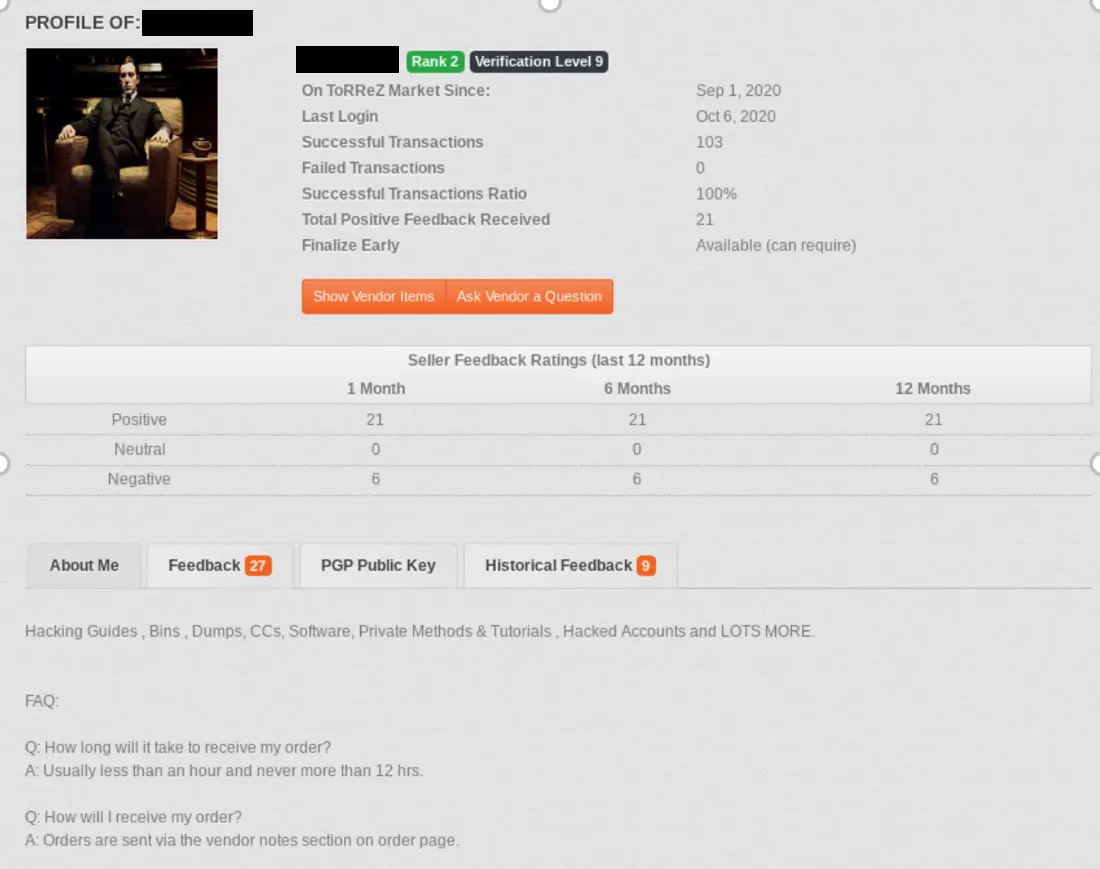

Honestly speaking, we don’t know, and we will probably never know who they are. But what we do know is that customer service exists on the Darknet. This means every vendor has a profile that shows all the items they sell, the feedback ratings they received on transactions and their services, the date since they are active on this market, as well when they last logged on (see screenshot 2). It is about reputation. Mostly when marketplaces disappear, and vendors must start over again, gaining trust and reputation on a new marketplace.

The Healthcare sector is usually one of the few verticals that suffers mostly from insider threats than external threat actors. This makes it difficult to detect in a mannerly time and detect it at all. Interestingly, the Verizon data breach investigations report 2020 shows that this might have shifted over the last year. According to the report, this is the first year we witness a small shift from insider threats towards external threats, such as an increase in ransomware attacks. Over the last year, this means misuse of privileges and combining forces with externals to conduct what they call “multiple actor breaches” has seen a decrease. If that trend is going to stay, and if that means that employees within the health sector will become more aware and educated on threats, only the future can tell. But it’s an interesting trend to observe that will hopefully continue.

Generally, the healthcare sector has seen an increase in successful ransomware attacks, where attackers threaten the victims to steal and publish health data. Especially over the past weeks and months, the healthcare sector seems to be a favorite target:

Other attacks besides ransomware where data was unintentionally leaked are:

Another attack type that healthcare is suffering from is web application attacks. According to Verizon’s data breach and investigations report, they don’t necessarily lead to stolen health data but are persistent. Like any other industry, the healthcare sector evolves and transfers aspects of its services into digital space to interconnect and interact with patients and other departments. Consequently, the attack surface becomes bigger and opens new opportunities for attackers.

While not directly relating to the medical sector, the COVID-19 pandemic was rapidly pivoted to as a lure in phishing attacks to play on people’s fear and curiosity around the ongoing crisis. This is a standard tactic used by threat actors in their phishing campaigns where an event or situation having a potentially global impact will be used to target potential victims. While there was a surge in COVID-19 related trends in phishing and spam emails early on in the pandemic, it is not thought that the total overall volume of phishing emails increased all that much. Amongst the trends being used are scams attempting to capitalize on shortages of PPI equipment such as masks and hand sanitizers and others advertising fake vaccines and cures. Another scheme piggybacked on an interactive map of Coronavirus infections published by Johns Hopkins University in an attempt to distribute malware.

As we have already alluded to, several cybercrime groups promised not to purposely target healthcare institutions during the pandemic, although this did not include all groups. Notably, there has been a reported increase in attempted attacks from nation-state actors targeting healthcare, pharmaceutical, and research organizations working on responses to COVID-19, such as vaccine and treatment development and research trying to find a cure. These attacks lead to joint alerts being issued by the United States F.B.I. CISA & UK’s NCSC is specifically mentioning Chinese and Russian APT groups.

One of the main factors for any organization can be the people they employ and who use their systems. In most cases, this is not because they are purposely malicious; instead, it is down to a lack of awareness regarding the risks and potential attack vectors associated with their day-to-day work. Regular, ongoing awareness training is essential to allow healthcare employees to identify suspicious activity, understand why certain security policies are necessary, and know what processes should be followed to report a potential security incident. Attackers routinely change tactics, and employees should be regularly updated to understand what to look out for. This is especially true where phishing attacks are concerned; using a simulated phishing attack service should be considered to prevent employees from becoming complacent.

An important area, but likely to be complicated within a health care environment, is ongoing vulnerability management of systems and applications. To mitigate the risk of systems being exploited requires a mature vulnerability management process to ensure relevant patches are promptly needed. This, in turn, requires an up-to-date inventory of deployed hardware and software assets to ensure full coverage when patches are deployed. While the day-to-day vulnerability management of PC’s and servers can be relatively easy, complications can arise when dealing with legacy software or hardware and devices with embedded systems, which can be difficult to patch or upgrade if it is even possible at all. To protect these kinds of systems, network segmentation should also be considered so that only trusted devices can access these high-risk systems across the network.

Authentication and authorization can be another problematic area. Any devices with default passwords should have them changed to new, unique, and complex passwords to prevent unauthorized access. For employee user accounts, the principle of least privilege should be applied to ensure they can only access the data and systems they require to perform their duties where possible single-sign-on solutions and multi-factor authentication should be put in place to help users and provide an additional layer of security.

Another option that should be considered is full disk encryption of systems used day to day by employees to ensure that any unauthorized person cannot access any sensitive data. This is especially true for laptops, which are more likely to be stolen or lost.

Diana Selck-Paulsson is a Threat Research Analyst at Orange Cyberdefense Sweden.

Carl Morris is a Lead Security Researcher at Orange Cyberdefense UK.

Christiaan Ileana is a Security Analyst at Orange Cyberdefense Netherlands.

Dennis Bijman is a Security Analyst at Orange Cyberdefense Netherlands.