Meet NailaoLocker: a ransomware distributed in Europe by ShadowPad and PlugX backdoors

Executive Summary

Authors: Marine Pichon, Alexis Bonnefoi

Acknowledgments:

Special thanks to Daniel Lunghi (Trend Micro) for his help on our ShadowPad analysis. His own investigation on this topic is available here.

Special thanks to Thomas Brossard from our CSIRT for his valuable forensic insights. This report is the result of a fruitful collaboration between teams inside Orange Cyberdefense CERT including the Incident Response team, World Watch and the Reverse Engineering Team.

- An unknown threat cluster has been targeting at least between June and October 2024 European organizations, notably in the healthcare sector.

- Tracked as Green Nailao by Orange Cyberdefense CERT, the campaign relied on DLL search-order hijacking to deploy ShadowPad and PlugX – two implants often associated with China-nexus targeted intrusions.

- The ShadowPad variant our reverse-engineering team analyzed is highly obfuscated and uses Windows services and registry keys to persist on the system in the event of a reboot.

- In several Incident Response engagements, we observed the consecutive deployment of a previously undocumented ransomware payload.

- The campaign was enabled by the exploitation of CVE-2024-24919 (link for our World Watch and Vulnerability Intelligence customers) on vulnerable Check Point Security Gateways.

- IoCs and Yara rules can be found on our dedicated GitHub page here.

Note: The analysis cut-off date for this report was February 15, 2025.

Introduction

Last year, Orange Cyberdefense’s CERT investigated a series of incidents from an unknown threat actor leveraging both ShadowPad and PlugX. Tracked as Green Nailao (“Nailao” meaning “cheese” in Chinese – a topic our World Watch CTI team holds in high regard), the campaign impacted several European organizations, including in the healthcare vertical, during the second half of 2024. We believe this campaign has targeted a larger panel of organizations across the world throughout multiple sectors.

Somewhat similar TTPs and payloads have been publicly mentioned in a write-up from HackersEye’s DFIR team.

In at least two cases, the intrusion ended up with the execution on victims’ systems of a custom, previously undocumented ransomware payload we dubbed NailaoLocker.

Our World Watch CTI team does not associate this campaign with a known threat group. Nevertheless, we assess with medium confidence that the threat actors do align with typical Chinese intrusion sets.

Infection chains

All four cases used a similar initial access vector consisting of the compromise of a Check Point VPN appliance. Our Incident Responders assess with medium confidence this was managed by the exploitation of CVE-2024-24919, a critical 0-day vulnerability affecting Check Point Security Gateways that have Remote Access VPN or Mobile Access features enabled (link to the Vulnerability Intelligence Watch advisory for our customers here). Patched in May 2024 but exploited in the wild since early April 2024 at least, the flaw enables threat actors to read certain information on gateways, and most importantly enumerate and extract password hashes for all local accounts. Due to the fact all observed Check Point instances were still vulnerable at the time of their compromise, CVE-2024-24919 likely enabled the threat actors to retrieve user credentials and to connect to the VPN using a legitimate account.

The threat actors then carried out network reconnaissance and lateral movement mostly through RDP, in an effort to obtain additional privileges. The threat actors were observed manually executing a legitimate binary “logger.exe” to side-load a malicious DLL,“logexts.dll” (T1574). When executed, the DLL copies an adjacent encrypted payload (for instance, “0EEBB9B4.tmp”) to a Windows registry key (with the name of this key being related to the system drive's volume serial number).

The “0EEBB9B4.tmp” payload is then deleted by the threat actors and ultimately retrieved by the DLL from registry key and injected into another process. Finally, a service or a startup task is created to run logger.exe and maintain system persistence. Upon analysis, we were able to associate “0EEBB9B4.tmp” to a new version of the infamous ShadowPad malware (with the DLL acting as its loader).

It should be noted we also observed very similar TTPs used to distribute PlugX around August 2024. In this specific case, threat actors used a legitimate McAfee executable called “mcoemcpy.exe” to side-load a malicious DLL (“McUtil.dll”). The DLL creates a Windows service for persistence and attempts to escalate privileges by using token-related APIs to grant itself the SeDebugPrivilege token. The loader then decrypts a third, highly obfuscated file called “Mc.cp” and injects the extracted shellcode into a launched but suspended process (Process Hollowing - T1055.012). Once injected, the process resumes execution to run the shellcode in memory. These three files correspond to the well-reported "PlugX trinity” execution workflow that can be created using one of the leaked PlugX builder available online.

ShadowPad analysis

ShadowPad is known for its widespread usage in cyberespionage campaigns against government entities, academic institutions, energy organizations, think tanks, or technology companies. This modular backdoor is suspected to be privately shared or sold among Chinese APTs since 2015 at least. In our cases, we identified what we believe is a new variant of ShadowPad featuring complexified obfuscation and anti-debug measures.

ShadowPad was observed establishing communication with a C2 server to create a discreet access point within the victims’ information systems that is independent of VPN access. In fact, we observed in some cases more than two weeks between these first stages of compromise and post-exploitation activities. It should also be noted that we retrieved indications that several ShadowPad backdoors were installed on different machines belonging to the same organization.

Infrastructure analyses

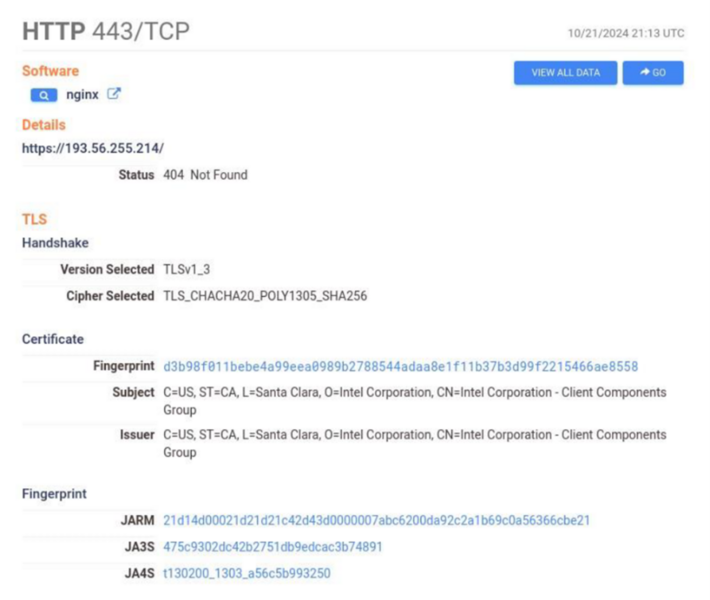

As previously exposed by CTI researchers, ShadowPad’s infrastructure is sometimes recognizable by its use of auto-signed TLS certificates attempting to spoof American technology companies. We can corroborate this observation since we encountered one C2 spoofing Intel Corporation and another one spoofing Dell Technologies.

- Figure 1: Censys information on IP 193[.]56.255.14 spoofing Intel Corporation

By pivoting on the certificates, we were able to retrieve additional IP addresses likely belonging to the same ShadowPad cluster. These have been included in the list of IoCs provided at the end of the report. All potential ShadowPad C2 servers span different Autonomous System, but many are hosted by VULTR.

Concerning the anonymization infrastructure used by the threat actors to connect to the Check Point VPN in the first place, we noticed one of the IP is a compromised IoT located in Sweden, potentially part of a botnet or ORB (Operational Relay Box) network. Another one is an exit node from Proton VPN.

Action on objectives and ransomware delivery

Orange Cyberdefense researchers observed the threat actors accessing files and folders and ultimately creating ZIP archives, suggesting data exfiltration attempts. In at least one case, we assess the threat actors notably captured the “ntds.dit” database file within Microsoft’s Active Directory, which typically stores user account details, passwords, group memberships, and other object attributes. Unfortunately, in several cases, limited firewall log retention and/or missing traffic details—such as packet sizes, session information, or data exchange volumes—restricted our ability to fully assess the exfiltration conducted by the threat actors.

The threat actors were then observed running a script targeting a list of local IP addresses and leveraging Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) to send three files to each host:

- “usysdiag.exe”,

- “sensapi.dll” (NailaoLoader),

- “usysdiag.exe.dat” (obfuscated NailaoLocker).

“usysdiag.exe” is a legitimate executable signed by Beijing Huorong Network Technology Co., Ltd, a Chinese security software provider. As “logger.exe”, the executable is used to side-load another DLL (“sensapi.dll”) and a data file “usysdiag.exe.dat” using a newly created Windows service named “aaa”

NailaoLoader analysis

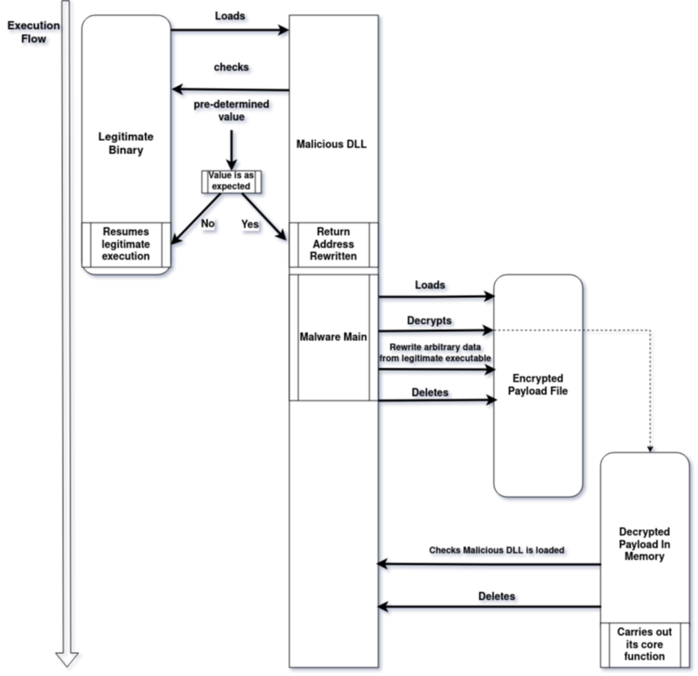

- Figure 2: Execution flow of NailaoLoader and NailaoLocker

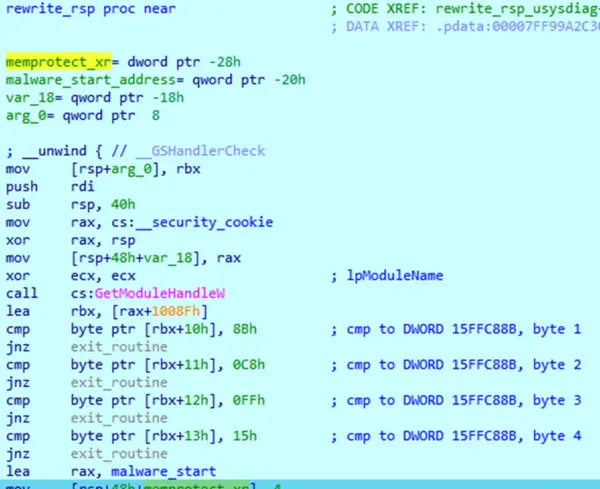

Once side-loaded, NailaoLoader DLL retrieves the calling module address with GetModuleHandleW API and performs checks for certain bytes values to ensure it is loaded by the right binary. This launches the malware routine. The controlled values are actually the return address of the LoadLibrary function call in the legitimate binary, which is then used to rewrite instructions and jump into the malware main function.

- Figure 3: sensapi.dll checks usysdiag.exe data to ensure it is loaded the expected way.

NailaoLoader’s loading method is quite straightforward. It first builds the payload filename, using GetModuleFilenameW API (“legit_binary_name.exe.dat”, such as “usysdiag.exe.dat”). It opens the .dat payload (NailaoLocker) with CreateFileW with RW access, gets the file size, and then decrypts the locker with the loop decrypted_byte = ((encrypted_byte + 0x4b ) ^ 0x3f) - 0x4b

- Figure 4: Payload decryption routine

We observed the exact same loop across multiple samples of NailaoLoader, but this loop can change in other campaigns.

The loader then writes random bytes data from the legitimate binary in the “.dat” payload, before removing the latter to prevent its recovery. NailaoLoader ultimately loads the decrypted NailaoLocker executable sections in a memory segment, gets imports, and jumps into its entry point.

NailaoLocker analysis

The locker first checks if sensapi.dll is loaded, then removes it from memory and deletes it from disk. It then creates the mutex “Global\lockv7”.

NailaoLocker creates a specific file to log what has been encrypted and what has failed, which was actually quite handy for our incident responders.

Written in C++, NailaoLocker is relatively unsophisticated and poorly designed, seemingly not intended to guarantee full encryption.

- it does not scan network shares,

- it does not stop services or processes that could prevent the encryption of certain important files,

- it does not control if it is being debugged.

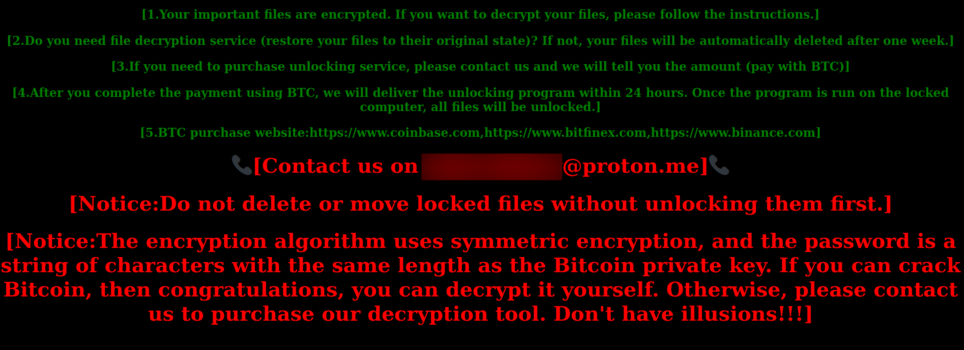

The ransomware uses the “.locked” extension and carries out asymmetric encryption through the AES-256-CTR algorithm. It drops a ransom note in:

“%ALLUSERPROFILE%unlock_please_view_this_file_unlock_please_view_this_file_unlock_please_view_this_file_unlock_please_view_this_file_unlock_please_view_this_file_unlock_please_view_this_file_unlock_please.html”

Finally, it loads it via “SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run”.

The ransom note includes typical extortion threats, asking the victim to reach out to a disposable Proton email address to purchase a decryptor in Bitcoin.

- Figure 5: Ransom note example left by NailaoLocker

Interestingly enough, by pivoting on the content of the ransom notes, we found other similar HTML files containing a link to a low-tier cybercriminal service provider known as “Kodex Softwares” (formerly Evil Extractor). The latter seems to procure three malware sold as-a-service since October 2022, which were advertised on the former Cracked and Nulled underground marketplaces. One of these tools feature ransomware capabilities against Windows systems. Nevertheless, the comparison of a Kodex ransomware sample from 2023 to our NailaoLocker samples revealed no code overlaps.

- Figure 6: Evil Extractor MaaS shop

Connecting Green Nailao to the larger Chinese threat ecosystem

As mentioned previously, we assess with medium confidence that the cluster do align with typical Chinese intrusion sets. This assessment is based on:

- The use of ShadowPad, an implant almost exclusively associated with Chinese targeted intrusion operations so far.

- The adoption of consistent TTPs, notably three-file execution chains with DLL search-order hijacking to execute the payloads (i.e., a legitimate executable vulnerable to DLL side-loading, a DLL loader and an encrypted payload). SecureWorks attributes some of these three-file execution chains to the BRONZE UNIVERSITY Chinese APT.

We also found some weak TTP overlaps with Cluster Alpha (STAC1248), a cluster mentioned in the 2023 Crimson Palace operation detailed by Sophos. Cluster Alpha was notably observed exploiting the very same “usysdiag.exe” legitimate application to sideload “SensAPI.dll”. Yet, in Sophos’ case, it appears the DLL is only used to load and execute a shellcode (“dllhost.exe”), before the DLL and the legitimate application are deleted. Sophos does not mention any ransomware deployment, with “dllhost.exe” instead allowing the establishment of a remote C2 session. Cluster Alpha is assessed with high confidence by Sophos to operate on behalf of Chinese state interests.

The deployment of a ransomware payload after the use of traditional cyberespionage tools is quite surprising. In that way, Green Nailao is very reminiscent of a recently published article from Symantec. Nevertheless, the cluster detailed by Symantec researchers slightly differs from Green Nailao as it involves the distribution of the RA World ransomware strain, a payload we did not observe across our different cases. Initially based on the leaked Babuk ransomware source code, RA World (or RA Group) is a double-extortion operation that surfaced in April 2023. In July 2024, the ransomware was tied with low confidence by Palo Alto to a Chinese threat actor known as BRONZE STARLIGHT.

Nevertheless, despite these various overlaps with known intrusion sets, we do not associate Green Nailao to a specific group. As of today, we are only able to raise several hypotheses on the final objectives of this campaign:

- The encryption and ransom demand could be used as a vocal false-flag distraction shifting attention away from the actual, more stealth goal of data exfiltration. Yet, the targets lacked strategic significance, making the attack an anomaly given the effort to obscure its intent. Additionally, the ransomware deployment poorly concealed the espionage-related backdoors.

- The ransomware is a way to kill two birds with one stone, with strategic data theft operation doubled with a profitable financially motivated extortion scheme. This combination, which for instance characterizes many North Korean cyberattacks, could aim at financing more strategic operations from the threat actors. Yet, based on our analysis of one of the wallets associated to the cluster, the latter do not appear to have made a lot of money with their cyberattacks.

- The ransomware as “on the side” moonlighting profitable scheme from a threat actor belonging to an advanced Chinese cyberespionage group or having access to its intrusion toolkit. This could help explaining the sophistication contrast between ShadowPad and NailaoLocker, with NailaoLocker sometimes even attempting to mimic ShadowPad’s loading techniques. This same hypothesis was also put forward by Symantec researchers and might be the most likely.

The targeting of healthcare-related entities by state-aligned groups, including from China, is not new. As recalled in the French national cybersecurity agency’s (ANSSI) Threat landscape for the healthcare sector, while such campaigns can sometimes be conducted opportunistically, they often allow threat groups to gain access to information systems that can be used later to conduct other offensive operations. Researchers from Mandiant for instance observed APT41 targeting US pharmaceutical entities in early 2020, meanwhile APT18 or APT10 have been historically tied to even older breaches affecting this vertical.

Conclusion

Thanks to a successful collaboration between analysts from several teams within Orange Cyberdefense CERT, we were able to document a new threat for European organizations. Suspected to emanate from a China-nexus intrusion set, the campaign we track as Green Nailao revealed new insights on the ShadowPad backdoor which had never been publicly linked to ransomware delivery before. This report also detailed a new ransomware payload we named NailaoLocker.

While this campaign seems to remain limited in terms of volume, it highlights the importance for organizations to apply security patches as soon as they are released.

Orange Cyberdefense’s Datalake platform provides access to Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) related to this threat, which are automatically fed into our Managed Threat Detection services. This enables proactive hunting for IoCs if you subscribe to our Managed Threat Detection service that includes Threat Hunting. If you would like us to prioritize addressing these IoCs in your next hunt, please make a request through your MTD customer portal or contact your representative.

Orange Cyberdefense’s Managed Threat Intelligence [protect] service offers the ability to automatically feed network-related IoCs into your security solutions. To learn more about this service and to find out which firewall, proxy, and other vendor solutions are supported, please get in touch with your Orange Cyberdefense Trusted Solutions representative.

The cybersecurity incident response team (CSIRT) in Orange Cyberdefense provides emergency consulting, incident management, and technical advice to help customers handle a security incident from initial detection to closure and full recovery. If you suspect being attacked, don’t hesitate to call our hotline.

Appendices

- ANSSI, https://www.cert.ssi.gouv.fr/cti/CERTFR-2024-CTI-010/

- Useful Censys query

- Cyber Peace Institute, https://cyberpeaceinstitute.org/report/2021-03-CyberPeaceInstitute-SAR001-Healthcare.pdf

- FireEye, https://dbac8a2e962120c65098-4d6abce208e5e17c2085b466b98c2083.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/beyond-compliance-cyber-threats-healthcare-pdf-10-w-5570.pdf

- HackersEye, https://hackerseye.com/dynamic-resources-list/tails-from-the-shadow-apt-41-injecting-shadowpad-with-sideloading/

- Hunt, https://hunt.io/blog/legacy-threat-plugx-builder-controller-discovered-in-open-directory

- Hunt, https://hunt.io/blog/tracking-shadowpad-infrastructure-via-non-standard-certificates

- Mandiant, https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/threat-intelligence/apt41-initiates-global-intrusion-campaign-using-multiple-exploits?hl=en

- Palo Alto, https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/ra-world-ransomware-group-updates-tool-set/

- SecureWorks, https://www.secureworks.com/research/shadowpad-malware-analysis

- SentinelOne, https://assets.sentinelone.com/c/shadowpad?x=p42eqa

- Sophos, https://news.sophos.com/en-us/2024/06/05/operation-crimson-palace-a-technical-deep-dive/#alpha-persistence

- Symantec, https://www.security.com/threat-intelligence/chinese-espionage-ransomware

- ThreatPost, https://threatpost.com/apt-gang-branches-out-to-medical-espionage-in-community-health-breach/107828/