The TrickBot and MikroTik connection

The TrickBot and MikroTik connection

In my professional capacity I perform several tasks. One task involves tracking and collecting indicators of compromise (IoC) used to identify malware campaigns. Another aspect of my work involves tracking incidents reported in mainstream media and then trying to establish trends while distilling the information into actionable items for clients and colleagues.

The fun part of my job involves writing tools or playing with tools authored by others. In this blogpost I describe where all these aspects neatly intersect and gives credence to work that our team has been doing.

Orange Cyberdefense tracks several malware campaigns, including one named TrickBot [1].

TrickBot is an information stealing malware that is typically delivered through phishing malspam. Several droppers are used to download the TrickBot malware. This is all done to improve chances of evading anti-malware and email filtering. One feature of the TrickBot malware is called web browser injection. This enables TrickBot to monitor web surfing activity of a victim. TrickBot will activate when certain web sites, such as Internet banking, are accessed. TrickBot attempts to capture account credentials of a victim when he or she browses to a login URL that is being monitored. Credentials or other information is captured and then exfiltrated to a Command and Control (C2) service.

If we look at industry trends, then one is definitely a contender on the top 10 offender list.

The definition of Internet of Things (IoT) is rather wide and expansive. It is typically used when referred to any device that is connected to a network such as the Internet. Some of these IoT devices are used to collect and stream sensor data. Other IoT devices, such as home routers, facilitates internet connectivity. IoT devices have become synonymous with poor security practices. This enables attacks that compromise and subvert these devices into what is called a botnet. A botnet is a group of compromised devices trained on serving the needs of the botnet operator.

Several botnet examples include Mirai, Satori, VPNFilter, and Slingshot. The latter two, VPNFilter and Slingshot, are purportedly linked to APT or nation state actors. Botnets like Mirai and VPNFilter have been associated with distributed denial of service attacks, while Slingshot was reportedly used to pivot into internal networks. As with most industries there exists confusing naming schemes and concepts. Malware campaigns such as TrickBot has no baring or relation to the concept of a botnets, in this case.

Orange Cyberdefense has been tracking botnets and found that several sources highlighted the increasing involvement of MikroTik devices in these botnets.

Several serious vulnerabilities have been identified in MikroTik firmware that saw various proof-of-concept (POC) code made publicly available. The availability of POC code and the reality of poor vulnerability management has meant an increase in the number of compromised MikroTik hosts.

On to the fun part.

The SD Labs team created a tool, named IOCParlor, that helps automate IOC collection and verification. IOCParlor is still in its infancy and a lot more work is needed before it can be considered fully functional. The existing capability of IOCParlor can extract IOC data from open source sources and this is feed into VirusTotal that helps gauge the quality of the IOCs. This qualification process minimises IOC volume and establishes a level of credibility of known bad indicators.

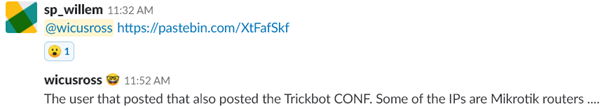

The team is constantly expanding its capabilities and tooling. Sometimes tools are born out of necessity, inspiration or idle curiosity. Enter my esteemed colleague, Willem. A few weeks prior to this blog, Willem saw that Pastebin, an online text sharing platform, was running a life-time Pro subscription promotion. Willem signed up and decided that he wanted to play with this toy. A couple of hours later saw the birth of a Pastebin scraper that hooked into a Slack and was aptly dubbed Pastebot.

It was not long before Pastebot started spamming our SD Labs Slack workspace with all kinds of nasties found on Pastebin.

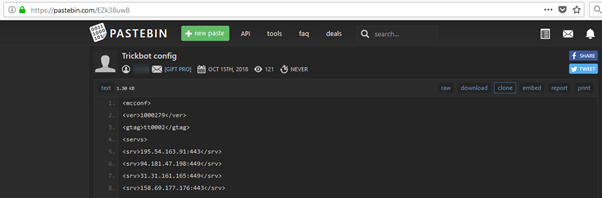

On that backdrop, we fast forward to one Monday morning just before lunch. I receive a Slack message from Willem with a link [2] to a Pastebin post that hosted XML config for a TrickBot campaign. This Pastebin post was picked up by Pastebot because Willem was looking for Pastebin posts that contain names of certain well established financial intuitions. The Pastebin post in question consisted of an XML file with 273 domains that resembles some sort of domain generation algorithm (DGA), but none of these were particularly interesting. Fortunately, the same user pasted another TrickBot XML file [3], that contained a TrickBot C2 config.

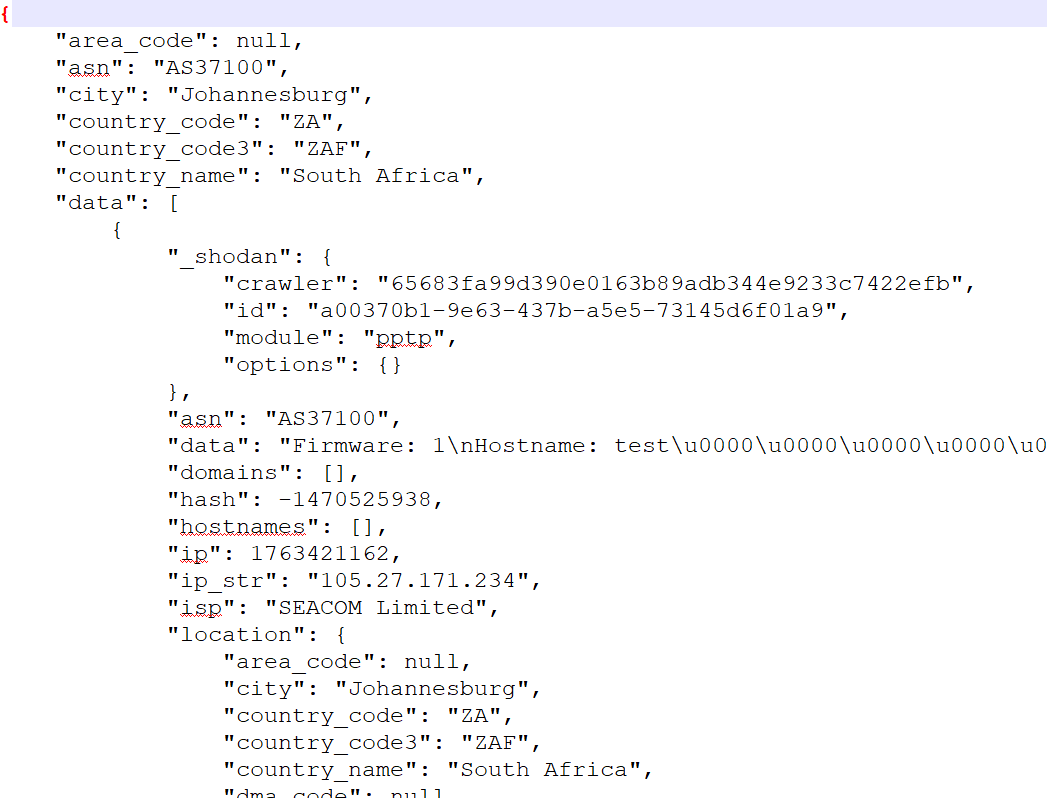

The config file contained 38 IP addresses and port pairs. A quick spot check of these IPs using Shodan provided us with a sense of what we were dealing with. As we hopped from one IP to the next we realised that several of the IPs are associated with MikroTik routers. To verify this, another quick Python script was thrown together that queried Shodan. The result was surprising. Of the 38 IPs, Shodan returned info on 37 hosts. Of the 37 hosts, 19 (51%) were identified as MikroTik routers. This suggests that either the routers have been compromised, or the hosts behind the routes have been compromised, or possibly both.

According to Shodan, the 19 MikroTik IPs have the following geographical distribution:

- Cambodia

- Colombia

- Ecuador

- Indonesia (3)

- Mexico

- Nepal

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russian Federation (2)

- South Africa

- Sweden

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United States (2)

Two of the MikroTik routers report firmware versions of 6.42.6 and version 6.42.7. The latter being the latest version and fully patched against known exploits. Of the 19 routers, 18 have default SSH ports exposed to the internet. The Shodan search result for the MikroTik router listed in the Philippines does not have any details of a SSH service listening. It is possible that this router might have its SSH service listening on a different port. If these routers were compromised, then it could have been done through password brute forcing of the admin account or any other default account.

All the MikroTik routers have their bandwidth test services exposed to the internet.

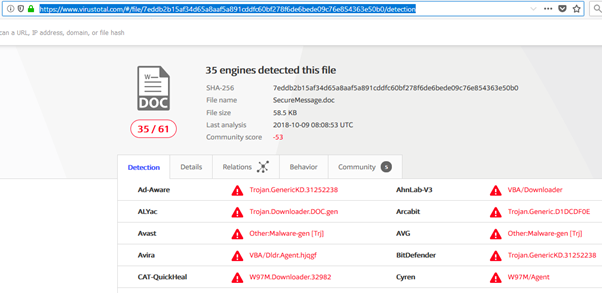

We took the 19 MikroTik router IPs and passed it through IOCParlor to get a sense of how naughty these hosts really are. IOCParlor queried VirusTotal and returned a list of 14 IPs that are flagged by 4 or more malware engines as malicious. To verify the results we picked an IP, 115.78.3.170 in this case, and manually reviewed using the VirusTotal [4] web client. Listed in the VirusTotal report is a MS Word document named SeucreMessage.doc. Of the 61 malware engines that scanned the document, 35 reported it as malicious.

Several of the malware engines classified the document as a trojan downloader, meaning that when Word opens the file it will download malware.

The community tab associated with the VirusTotal report had several annotations. One comment is by dvk01 of My Online Security, a phishing and malware campaign reporting site that the SD Labs team regularly use as part of its IOC gathering process. The user dvk01 labelled the malware as TrickBot and links to an article that mentions the same contagion. The My Online Security article [5] describes the TrickBot phishing email and shows the malicious Bank of America email with a malicious document that is accessed through an URL in the email.

In September 2018 SecureData published a Threat Advisory highlighting the increasing number of MikroTik routers that are ensnared in malicious activity. What we found interesting is that TrickBot, an info stealing malware, is using C2 hosts that have MikroTik routers involved somehow. Seeing how all of this played out in relation to SecureData activities of the past few months provides a sense of validation and a feeling of affirmation. With this simple example we have once again reaffirmed the benefits of continued investment in research and tooling.

The fact that we can leverage several seemingly unrelated events and tie it together with other analysis helps SecureData to make better informed decisions that deliver quality service to our customers.

More about the author:

Wicus Ross, Lead Researcher, Orange Cyberdefense

Wicus investigates industry events and trends with the single purpose of understanding how incidents may affect Orange Cyberdefense’s clients and how to best guard against it. Wicus was previously involved with software development and compliance at an e-commerce technology vendor.

References:

[1] https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/details/win.trickbot

[2] https://pastebin.com/raw/XtFafSkfF (Removed/Expired)

[3] https://pastebin.com/raw/EZk38uw8

[4] https://www.virustotal.com/#/file/7eddb2b15af34d65a8aaf5a891cddfc60bf278f6de6bede09c76e854363e50b0/detection

[5] https://myonlinesecurity.co.uk/trickbot-via-fake-bank-of-america-secure-message/